America's Public Lands: What, Where, Why, and What Next?

For many people, upon hearing the term “America’s public lands,” the national parks come immediately to mind, and for good reason. The national parks form the crown jewel of the system of public lands in the United States, as illustrated in Figure 1 of the Grand Canyon. When President Theodore Roosevelt first saw the canyon in 1903, he stated: “Let this great wonder of nature remain as it now is. Do nothing to mar its grandeur, sublimity and loveliness. You cannot improve on it. But what you can do is to keep it for your children, your children’s children, and all who come after you, as the one great sight which every American should see” (History.com Staff 2009, 1). The Grand Canyon was not a national park when Roosevelt made that statement, but he used the power of his office to initiate a process by which it became one of the earliest national parks in the country. Roosevelt acted to ensure that this “great sight” would be preserved for future generations despite opposition from powerful development interests, and the National Park Service (NPS) has continued that very thing for over 100 years. But public lands in the United States do much more that preserve awe-inspiring natural environments for posterity, and the system of public lands serves a range of conservation as well as preservation purposes.

Yet federal ownership and management of the lands has met considerable resistance both in the past and today. Campaigns have attempted to turn the federals lands over to the states or even to privatize them. In 1946--1947, the first so-called “sagebrush rebellion” attempted to do just that. But writing in Harpers, historian and essayist Bernard DeVoto rallied opposition: "The plan is to get rid of public lands altogether, turning them over to the states, which can be coerced as the federal government cannot be, and eventually to private ownership. . . Nothing in history suggests that the states are adequate to protect their own resources, or even want to, or suggests that cattlemen and sheepmen are capable of regulating themselves even for their own benefit, still less the public’s" (DeVoto 1947, 9). With the public’s support, the federal lands remained intact at that time. But the debate rages and continues to the present. The focus of this article is to help inform the debate with a brief overview of what the public lands are, where they are located, why they exist, and what they face in the future.

Public Lands: What and Why?

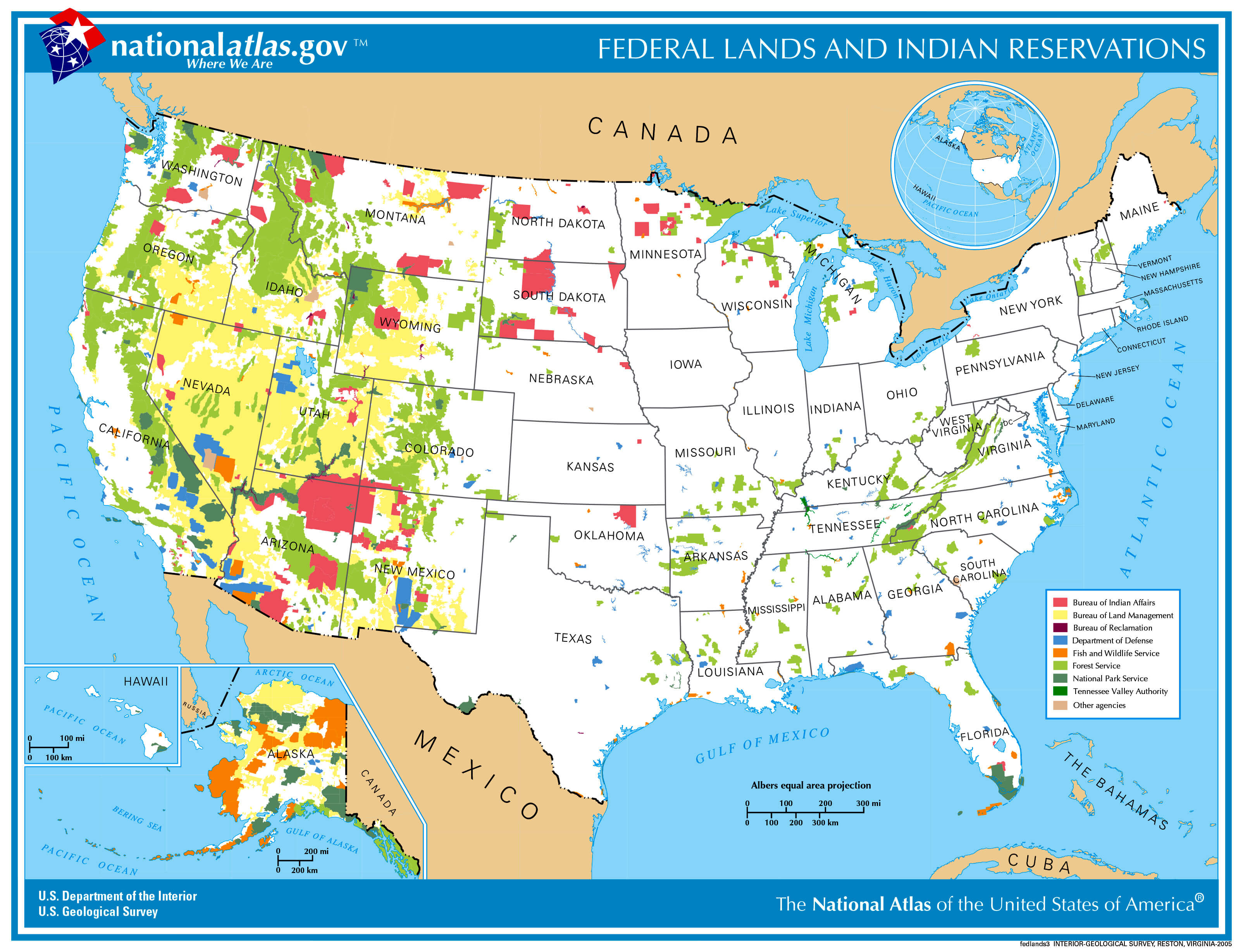

While public lands exist at state and local levels as well as federal, the focus in this article is on federal public lands. Four agencies carry primary responsibility for managing these lands that stretch across the United States, each with its own unique mission within the larger public-lands system (Figure 2). It is important to understand America’s public lands as a system of separate but interrelated components. While development of such a system was not generally intended historically, what emerged and persists today is an arrangement for managing public lands to meet a variety of purposes (Wilson 2014). Within the system there are two distinct purposes: preservation and conservation. Preservation entails maintaining natural environments in their present condition and as untouched by humans as possible, while conservation involves the sustainable use and management of natural environments and their resources to meet the needs and interests of people now and into the future (Wilson 2014).

The NPS focuses on preservation of natural environments and cultural heritage, and upon fostering public visitation and appreciation of these places. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) works to preserve habitat for wildlife, conservation of the resources, and maintenance of biological diversity. It also manages the National Wildlife Refuge System. The United States Forest Service (USFS) has primarily a conservation mission that advances multiple, sustainable uses of the environment for activities including forestry, grazing, mining, watershed regulation, and recreation, along with some ecological preservation. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has historically managed land for extractive resource development, and while this remains a priority, the agency is increasing its emphasis on multiple use, with particular emphasis on identification of special areas for conservation and restoration. Toward this latter end, the agency manages the National Landscape Conservation System (now known as the National Conservation Lands) (Wilson 2014).

Public Lands: Where and Why?

The map in Figure 3 from the National Atlas shows the distribution of federal lands across the United States. The four main land-management agencies are displayed, along with various other agencies that do not principally manage land for either preservation or conservation purposes. Federal land ownership is concentrated in the West, in part reflecting the settlement history of the country. The Eastern states were established at the country’s founding. Away from the coast, the federal government’s priority was to “dispose” of the lands, that is, to form new states where settlement and use by the country’s growing population and expanding economy could occur. Most lands in the West were acquired later in U.S. history through purchase or conquest. While the federal government still formed states in the West as part of its mandate to “dispose” of the lands, much of the land was not suitable for the agriculture that made so much of the more Midwestern lands attractive to private interests, and so it remained in public hands. The U.S. Constitution specifically states that such unowned lands did not automatically transfer to the states, but rather, the federal government retained authority over them (Wilson 2014).

The mission of the National Park Service to preserve awe-inspiring natural landscapes is well illustrated by Yosemite National Park, which was established in 1890 as the country’s second national park. The top photo in Figure 4 shows the granite cliffs of Yosemite Valley that were carved by glaciers and rise over 3,600 feet above the floor of Yosemite Valley (NPS 2017A). The photo on the right shows the vertical granite walls of the valley, while the bottom photo shows the Tenaya Lake area in the Yosemite high country, with the lake surrounded by granite domes, forests of lodgepole pine, and Yosemite’s vast wilderness (NPS 2015; Yosemite Mariposa County 2018).

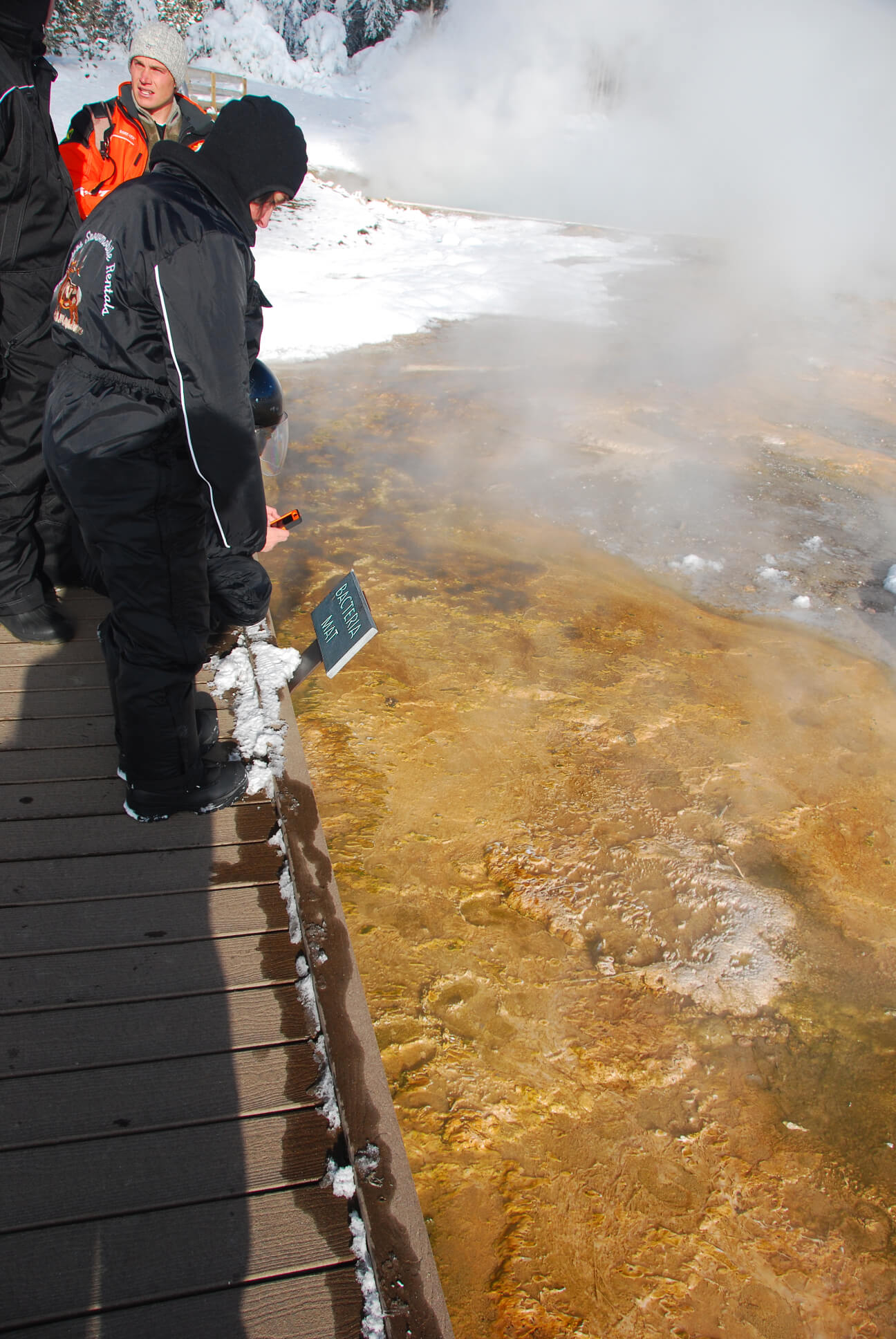

Grand Teton National Park (NPS 2017B) is preserved by the NPS as one of the crown jewels of America’s public lands, and it borders another one, Yellowstone National Park (NPS 2018A). Both parks are surrounded by USFS lands, and taken all together, these lands form the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, one of the largest, nearly intact temperate-zone ecosystems on earth that contains the largest concentration of wildlife in the lower forty-eight states. In the top photo in Figure 5, the Snake River runs along the eastern side of the Teton Range. The bottom photos show the landscapes, geysers, hot pools, and wildlife of Yellowstone.

Figure 6 is a view of Badlands National Park from the south at sunset, and it shows the strikingly beautiful geologic formation that is preserved as a national park and that also comprises one of the world’s richest fossil beds (NPS 2018B). The park also preserves one of the largest undisturbed, mixed-grass prairie ecosystems in the United States along with considerable numbers of wildlife species.

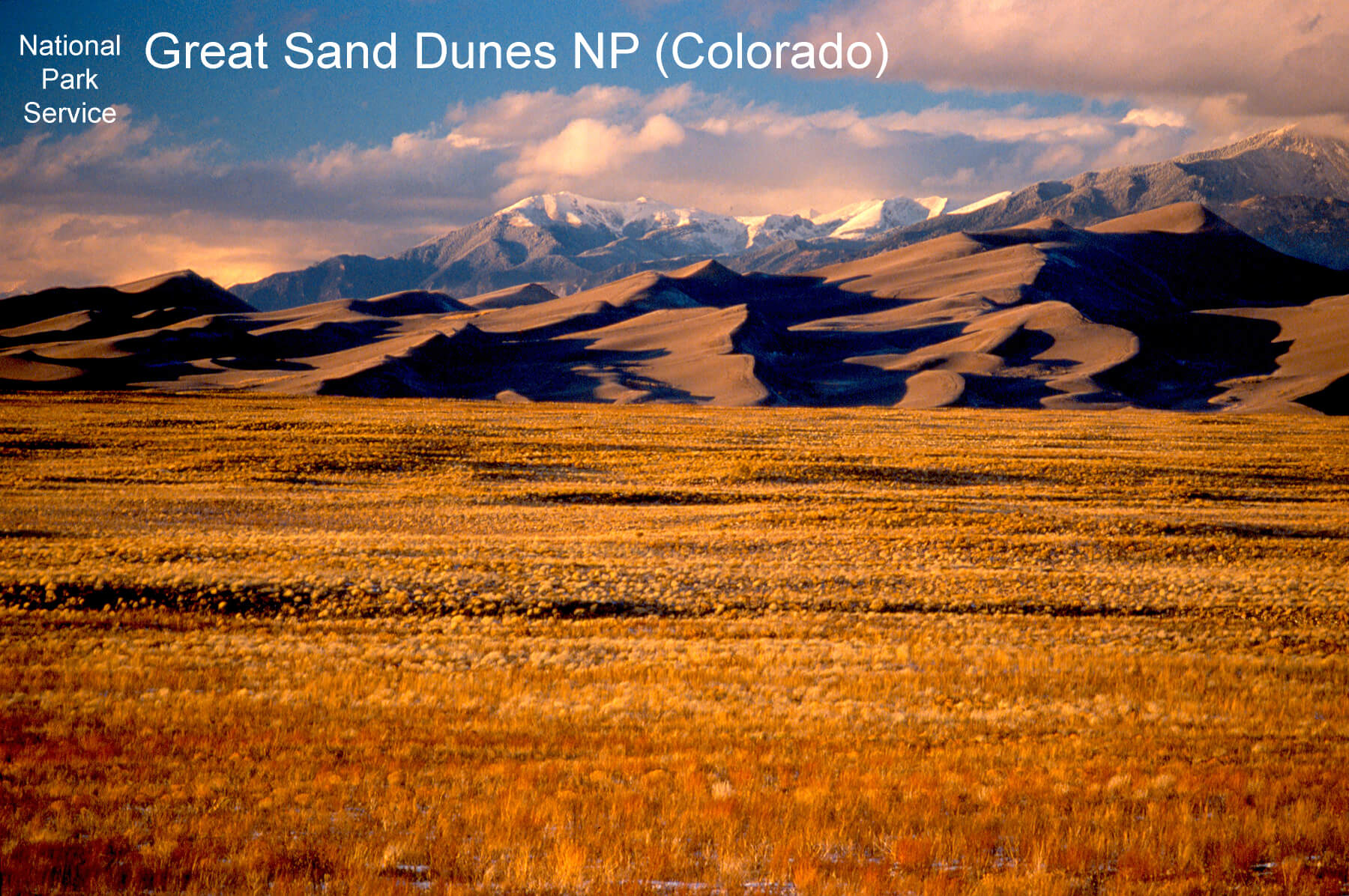

Great Sand Dunes (Figure 7) preserves the highest dunes in North America and it extends to the crest of Colorado’s Sangre de Christo Range, which lies behind. These boundaries preserve a wide range of ecosystems, beginning with the grasslands, shrublands, and dunes with an elevation of over 7,500 feet at the base of the mountains and rising up through the riparian, montane forests/woodlands, subalpine forest/meadows, and alpine tundra that emerge with the increasing elevation along the slopes of the mountains to over 13,000 feet NPS 2016).

Olympic National Park (Figure 8) preserves ecosystems in pristine condition, such as the rugged, cliffed Pacific shore and a temperate rainforest (NPS 2017C). The top photo shows the huge logs that are deposited along the beach after floating down the raging rivers in this high rainfall zone. The bottom photo shows Tatoosh Island, which lies offshore from Cape Flattery, the westernmost point in the forty-eight contiguous states. The park has been recognized internationally by UNESCO as an International Biosphere Reserve and World Heritage Site, and as such, is legally protected by international treaties as well as by the U.S. government (UNESCO 2018).

Organ Pipe is a “monument,” not a “park” even though it is a unit of the NPS and fulfills a preservation mission (NPS 2017D). National parks result from legislation passed by Congress and signed into law by a president while national monuments are established by presidential proclamation under authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906 (Wilson 2014). Parks are as close to permanent as possible in the U.S. system of government, but the status of monuments is more uncertain. Some monuments, such as Organ Pipe pictured in Figure 9 at sunset with silhouettes of the organ pipe and saguaro cacti of the Sonoran Desert ecosystem, are managed by the NPS and have very secure status. But national monuments can be managed by any of the federal public-lands agencies, and recently the status of some of them is being disputed.

While the national parks receive permanent legislative designation, funding for them, as for all public lands, comes from the domestic, discretionary portion of the federal budget, and as such, is subject to the annual appropriations process in which Congress and the president allocate specific amounts of funding. As the most well-known and visible public lands, the funding level for national parks (and the monuments within the NPS) will likely be adequate to retain the preservation and public awareness mission, but some modification may occur. For example, recent efforts by the secretary of the interior have called for allowing drilling for natural gas in national parks, something never before allowed or seen as part of their mission.

Lands managed by the USFWS include those of the 560 units within the National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) system, many of which lie along one of the north-south “flyways” for migratory birds. The Bosque del Apache NWR (Figure 10) lies on the Rio Grande River and serves as wintering ground for various bird species including the snow geese and sandhill cranes shown here. Because the Rio Grande has been dammed extensively and the water diverted for irrigation of farms, the natural cycles of alternating floods and slack-water periods no longer provide the habitats in which these birds and other wildlife can flourish (USFWS 2017). Consequently, this refuge is managed to mimic those natural cycles by use of small canals, gates, and dams that flood and drain areas on seasonal schedules. In addition to management of the NWR system, the USFWS performs a wide range of additional, primarily conservation services: working with private landowners to establish easements that help to conserve and restore wildlife habitat, determining species that are endangered or threatened and developing plans for their protection, protecting and restoring fisheries and operating fish hatcheries, determining appropriate levels of hunting and fishing to allow and overseeing such use, and enforcing federal wildlife laws (Wilson 2014).

The Tallahatchie NWR (Figure 11) is part of a complex that consists of bottomland hardwood trees, early successional reforestation areas, various fields, and moist soil units that are located in the low-lying lands of the Mississippi Delta region. Bisected by the meandering Tippo Bayou, the Tallahatchie NWR is managed to conserve and restore the historically extensive forested wetlands of this region, which has been largely deforested and drained for commercial agricultural production (USFWS 2014). This kind of habitat conservation and restoration is a primary goal of the USFWS.

As with all public lands, the USFWS is funded through annual appropriations in the domestic, discretionary portion of the federal budget, and consequently, the agency competes continually against other domestic priorities for funding to advance its mission. In addition to the overall funding level, however, Congressional and presidential priorities can change with different political makeups and result in different emphases among the components of the agency’s mission. For example, emphasis could shift between maintenance of habitat for endangered species and use of the resource for hunting, fishing, and increased public access.

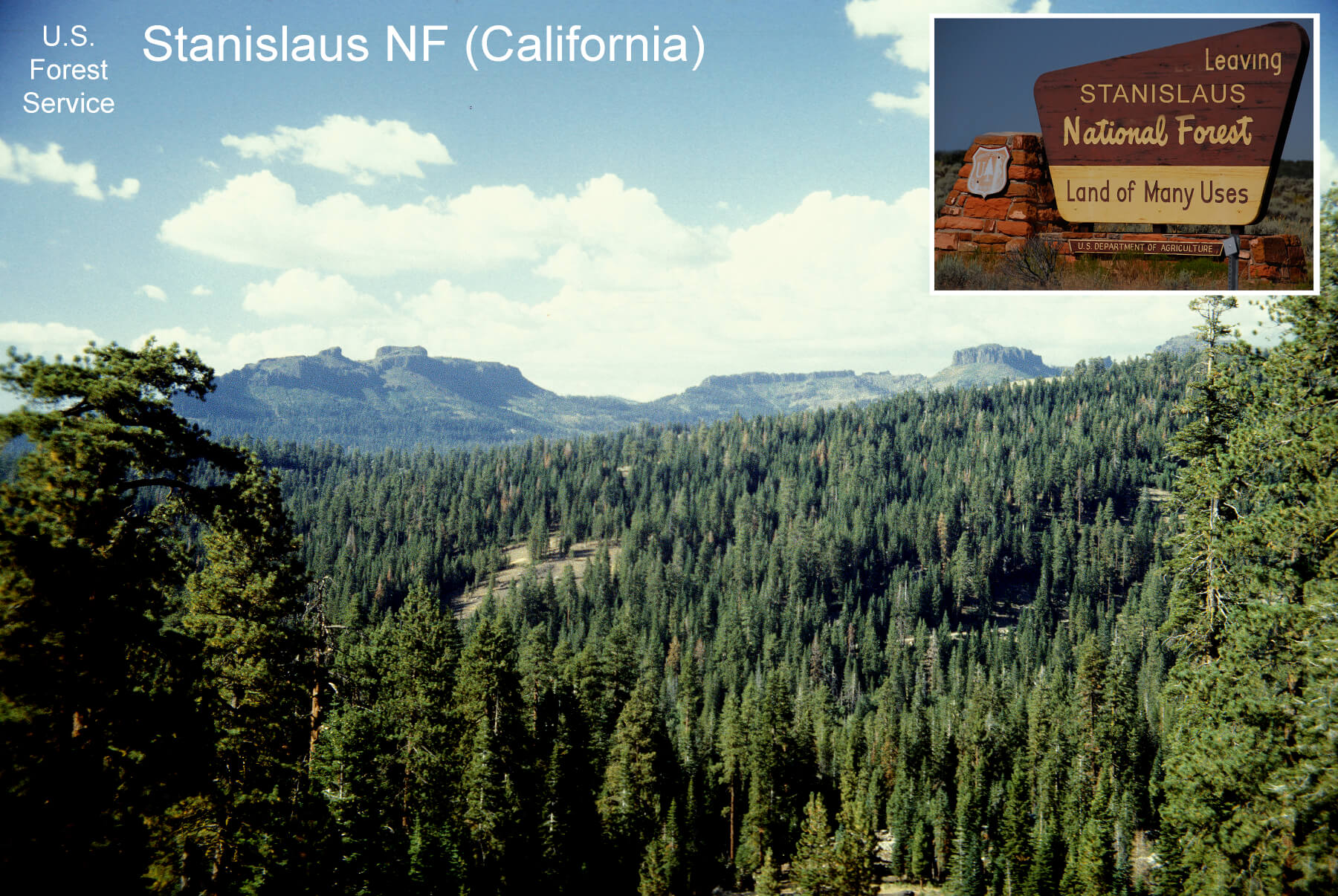

The USFS was created in 1905 when previously established forest reserves were consolidated into one agency with a clear conservation mandate. As the name implies, a primary mission of the USFS is to manage the nation’s forests (Figure 12), protecting them from wastefulness and ensuring sustainable timber yields. This mission considers forests to be a form of agriculture, and consequently, that is one important reason for housing this agency in the Department of Agriculture. Livestock grazing and hunting are also considered agricultural pursuits and form part of the “multiple use,” conservation mission well expressed in the USFS motto, “Land of Many Uses.” Recognizing the conflicting interests that would arise through this “multiple use” mission, Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the USFS, stated, “[W]here conflicting interests must be reconciled, the question shall always be decided from the standpoint of the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run,” another motto of the USFS (Lewis 2005).

One of the main functions of national forests is to conserve watersheds in the forested mountains so as to mitigate flooding in the rainy season and ensure a steady supply of water to the valleys throughout the year. The top photo in Figure 13 shows the Taylor River as it flows through the Gunnison NF while the bottom photo shows the Surprise Valley in California that lies below the forested slopes of the Warner Range in Modoc NF. Agricultural lands lie downstream from many of the USFS lands and those agricultural lands benefit substantially from the forest and watershed management practiced by the USFS. The national forest lands provide this public good to the private-sector, agricultural interests and this highlights the important public/private relationships that exist in conservation efforts. This also emphasizes another reason why the USFS finds its home in the Department of Agriculture.

Important parts of the “multiple use” mission of the USFS include restoration and preservation. The photo on the left in Figure 14 shows restoration of the endangered black-footed ferret, while the photo on the right shows a trailhead into a wilderness area. Signed into law in 1964, the Wilderness Act recognized wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain” (Public Law 88-577 1964, 891). While wilderness areas have been established in all four of the public lands agencies, most wilderness areas are managed by the USFS (USFS 2013).

Recreation is an important part of the “multiple use” mission of the national forests. Recreation encompasses many uses and includes exploring by four-wheel-drive vehicles, bicycles, river rafts, horseback, and backpacking on foot (Figure 15). Similar to NPS and the USFWS, the USFS continually vies for funding in the domestic, discretionary portion of the federal budget, and it could see changes in its land-management priorities, resulting from changing political orientations in the federal government. For example, how might the balance between grazing, logging, mining, recreation, and wilderness preservation in the USFS multiple-use mission change?

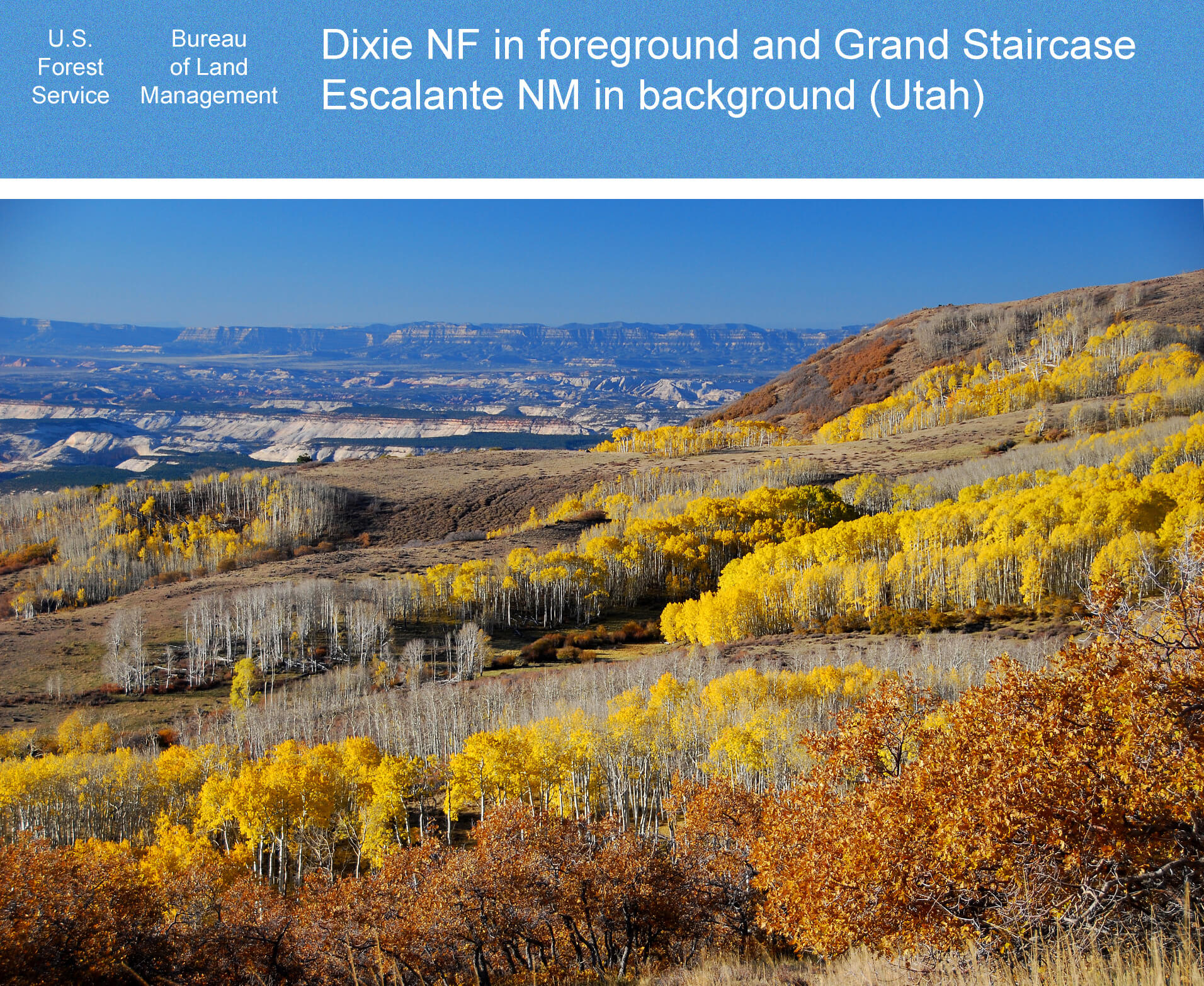

Much of the Aquarius Plateau shown in the foreground of Figure 16 lies on USFS land above 11,000 feet elevation. The USFS manages this forested land for the full range of multiple use purposes. The BLM manages the land in the background of the photo as the Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument.

This view in Figure 17 is from the Kaibab Plateau in Arizona looking north toward the Grand Staircase with its distinctive brightly colored cliffs that rise 5,500 feet and display 275 million years of geologic history. Most of the area is preserved as federal public land, with much of it in Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument (GSENM). The monument was established in 1996 on BLM land by presidential proclamation under the Antiquities Act, which states that monuments be established to protect, in part, objects of “scientific interest” and that monument size must be the “smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected” (Public Law 59-209 1906, 464). Debate swirls around the size of GSENM. On December 4, 2017, President Trump signed a proclamation reducing the boundaries of this monument, but lawsuits were filed immediately challenging the action. The lawsuits maintain that the Antiquities Act gives presidents authority to create a national monument, but only Congress can revoke or reduce one. Whatever the outcome of this legal battle, a key question remains: what is the smallest size needed to protect this landscape of the Grand Staircase of Western Geology as an “object of scientific interest?”

The BLM was created comparatively recently, in 1946, from a merger of existing federal agencies that centered on grazing and mining (Wilson 2014). As can be seen in Figure 18A, the agency’s early logo showed a surveyor, logger, engineer, rancher, and miner standing shoulder to shoulder and symbolizing how the BLM retained an emphasis on resource extraction and development. Behind the men is a wagon train on the open prairie, suggesting the past while in front of them lies a landscape symbolic of the imagined, developed future of railroad tracks, buildings, and other infrastructure. But a few years later, the so-named “environmental decade” of the 1960s saw the rise of considerable efforts to address environmental issues. In response, the federal government changed and expanded its priorities, with specific impacts on federal land-management agencies, including the BLM. While the logo changed in 1964 to reflect the new priorities (Figure 18B), it was only in 1976 that the agency received a legislated mission from Congress to incorporate sustainable-yield principles and multiple-use values based on “scientific, scenic, historical, ecological, environmental, air and atmospheric, water resource and archeological” considerations (BLM 2001, 1).

The BLM manages the National Conservation Lands that are areas identified as ecologically rich and culturally significant. Ten designations exist and include National Monuments, National Conservation Areas, Wilderness and Wilderness Study Areas, Wild and Scenic Rivers, and National Scenic and Historic Trails. Established originally by the Department of Interior in 2000 and then legislated by Congress in 2009, this system recognizes that genuine conservation of natural and cultural resources entails protecting large areas that cover entire ecosystems and archaeological communities (BLM 2018; Conservation Lands Foundation 2018). Figure 19 shows one of these units.

But public lands managed by the BLM, including the National Conservation Lands, are perhaps the most vulnerable to changing political orientations that may shift efforts increasingly from conservation and toward resource extraction, especially given the agency’s heritage as focused on development, its considerable acreage, and its many national monuments. And as with the other parts of the system, the BLM is also subject to annual appropriations that could squeeze its efforts.

Why and What Next for the Public Lands?

Federal public lands have been an inseparable part of American life since the country began. They played an essential role in establishment of the Articles of Confederation following the Revolutionary War when the former colonies only agreed to form a republic by ceding to the nascent federal government much of their claims to land extending from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River. Federal authority over public lands was strongly reinforced a few years later in the Constitution which also stipulated that a primary goal of Congress was to “dispose” of the public lands to private interests for development of the country and its economy. This goal persisted throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth in forms such as the Homestead Act, federal railroad grants, and other actions. But change in the purpose of public lands began to emerge even in the early twentieth century, as illustrated by President Roosevelt’s words in 1903 that the Grand Canyon was a “great wonder of nature [that should] remain as it now is.” The ideas of conservation and preservation of public lands grew with establishment of the USFS in 1905 and the NPS in 1916, agencies that advanced conservation and preservation goals throughout the twentieth century. Figure 20 helps illustrate both these goals, with forest and watershed conservation shown in the foreground while preservation of high mountain wilderness areas is visible in the background.

The “environmental decade” of the 1960s amplified recognition that public lands could play a crucial role in retaining a natural world that was diminishing in the face of the dominant economic expansionist development paradigm that depended on resource extraction and use. In 1976, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) established law that formally reversed the policy of land “disposal” by recognizing the value of public lands and declaring that they should remain in public ownership (Public Law 94-579 1976).

Today in the United States, public lands are torn between paradigms of preservation, conservation, and development. The development paradigm did much to improve the country during the nineteenth and much of the twentieth centuries, but in recent decades, it seems to be producing diminishing marginal returns. Yet human striving to maintain that development paradigm is resulting in increased pressure to curtail preservation efforts and to exceed levels of sustainable conservation. America faces questions about the kinds of improvements that are best suited to conditions in contemporary times and public lands are integral to the answers that develop. The balance between continued or amplified extractive development and attention to preservation and conservation will continue to be played out on the public lands.

References

- BLM (Bureau of Land Management). 2001, Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 As Amended. Denver CO: Bureau of Land Management. [https://www.blm.gov/or/regulations/files/FLPMA.pdf].

- ________ 2018. National Conservation Lands. Washington DC: Bureau of Land Management. [https://www.blm.gov/programs/national-conservation-lands].

- Conservation Lands Foundation. 2018, About the National Conservation Lands. Durango CO: Conservation Lands Foundation. [https://conservationlands.org/conservationlands/about-the-national-conservation-lands]

- DeVoto, B. A. 1947. The West Against Itself. The Harpers Monthly, January: 1-13. [http://mdevotomusic.org/?p=94].

- History.com Staff. 2009. Roosevelt Dedicates the Grand Canyon as a National Monument. New York: A+E Networks. [http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/roosevelt-dedicates-the-grand-canyon-as-a-national-monument].

- Lewis, J. G. 2005, The Forest Service and the Greatest Good: A Centennial History. Durham NC: The Forest History Society.

- Munn, J. and H. R, Stuart. 1988. Opportunity and Challenge: The Story of BLM. Washington DC: Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management. [https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/blm/history/chap3.htm]

- NPS (National Park Service) 2015. Tenaya Lake Area Plan. Yosemite National Park CA: Yosemite National Park. [https://www.nps.gov/yose/learn/management/tenaya.htm]

- ________ 2016. Natural Features and Ecosystems. Mosco CO: Great Sand Dunes National Park & Preserve. [https://www.nps.gov/grsa/learn/nature/naturalfeaturesandecosystems.htm].

- ________ 2017A. Yosemite. Yosemite National Park CA: Yosemite National Park. [https://www.nps.gov/yose/index.htm].

- ________ 2017B. Mountains of the Imagination. Moose WY: Grand Teton National Park. [https://www.nps.gov/grte/index.htm].

- ________ 2017C. Discover Olympic’s Diverse Wilderness. Port Angeles WA: Olympic National Park. [https://www.nps.gov/olym/index.htm].

- ________ 2017D. Life Abounds in the Sonoran Desert. Ajo AZ: Organ Pipe National Monument. [https://www.nps.gov/orpi/index.htm].

- ________ 2018A. Marvel. Explore. Discover. Yellowstone National Park WY: Yellowstone National Park. [https://www.nps.gov/yell/index.htm].

- ________ 2018B. Good Times in the Badlands. Interior SD: Badlands National Park. [https://www.nps.gov/badl/index.htm].

- Public Law 59-209 (16 USC 431-433). 1906. American Antiquities Act of 1906. [https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2011-title16/pdf/USCODE-2011-title16-chap1-subchapLXI-sec431.pdf]

- Public Law 88-577 (16 U.S.C. 1131-1136). 1964. The Wilderness Act. [https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-78/pdf/STATUTE-78-Pg890.pdf].

- Public Law 94-579 (43 U.S.C. 1701-1787). 1976. Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, [https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-90/pdf/STATUTE-90-Pg2743.pdf]

- PLF (Public Lands Foundation). No Date. Bureau of Land Management - Official Shield / Logo of the DOI / BLM old design. Washington DC: Public Lands Foundation. [https://publicland.org/plf-archives/35_archives/photos/0001-9000/1295.jpg]

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization). 2018. Olympic National Park. Paris: UNESCO. [http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/151;].

- USFS (United States Forest Service). 2013, Wilderness. Washington DC: USDA Forest Service [https://www.fs.fed.us/managing-land/wilderness]

- USFWS (United States Fish and Wildlife Service). 2014. About the Complex. Grenada MS: Tallahatchie National Wildlife Refuge. [https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Tallahatchie/About_the_Complex.html]

- ________ 2017. Resource Management. Socorro NM: Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge. [https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Bosque_del_Apache/what_we_do/resource_management.html]

- USGS (United States Geological Survey). 2007. The National Map. Reston VA: USGS. [https://nationalmap.gov/small_scale/printable/fedlands.html#list].

- Wilson, R. K. 2014. America’s Public Lands: From Yellowstone to Smokey Bear and Beyond. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Yosemite Mariposa County. 2018. Tenya Lake. Mariposa CA: Yosemite Mariposa County Tourist Bureau. [https://www.yosemite.com/what-to-do/tenaya-lake/].