Hurricane Dorian and Landscapes of Recovery in the Bahamas

Jordan R. Cissell, Department of

Geography and Sociology, Samford University

DOI: 10.21690/foge/2021.64.2p

Introduction

Hurricane Dorian made landfall on the Abaco Islands and Grand Bahama Island of the Bahamas between

September 1 and September 3, 2019. This three-day storm event is now recognized as one of the most

destructive natural disasters in Bahamian history, with at least 70 confirmed deaths, more than 200

people unaccounted for, and more than $3.4 billion USD in property damages (Zegarra et al. 2020).

Just as Dorian destroyed human life and property on Abaco and Grand Bahama, it also devastated the

islands’ coastal ecosystems, particularly its mangrove forests. The livelihoods of many Bahamian

communities are closely tethered to the health of these coastal ecosystems, particularly through

food from subsistence fishing; income from commercial fishing; and income from recreational fishing,

diving and snorkeling, and other tourist activities. Therefore, the ongoing recoveries of these

people and landscapes are intimately and reciprocally linked.

In February 2020, Michael Steinberg and I conducted field work on Grand Bahama as part of an ongoing

effort to map Dorian’s impacts on mangrove and pine forests on Grand Bahama and Abaco using

high-resolution satellite imagery. While the “bird’s eye view” of satellite imagery is useful for

accurately and efficiently mapping the extent of the hurricane damage, nothing can compare with “on

the ground” observation for appreciating the intensity of the storm’s impact. In this photo essay, I

share images from our field work to illustrate the severity of Dorian’s impact on the people and

environments of Grand Bahama and Abaco, the importance of these landscapes to local communities, and

the daunting task of recovery faced by these communities.

Because we conducted all of our field work on Grand Bahama, photos and anecdotes from Grand Bahama

are the focus of this photo essay. However, because the ecosystems and livelihoods of Abaco are very

similar to those of Grand Bahama, Grand Bahama’s story is highly representative of Abaco’s story.

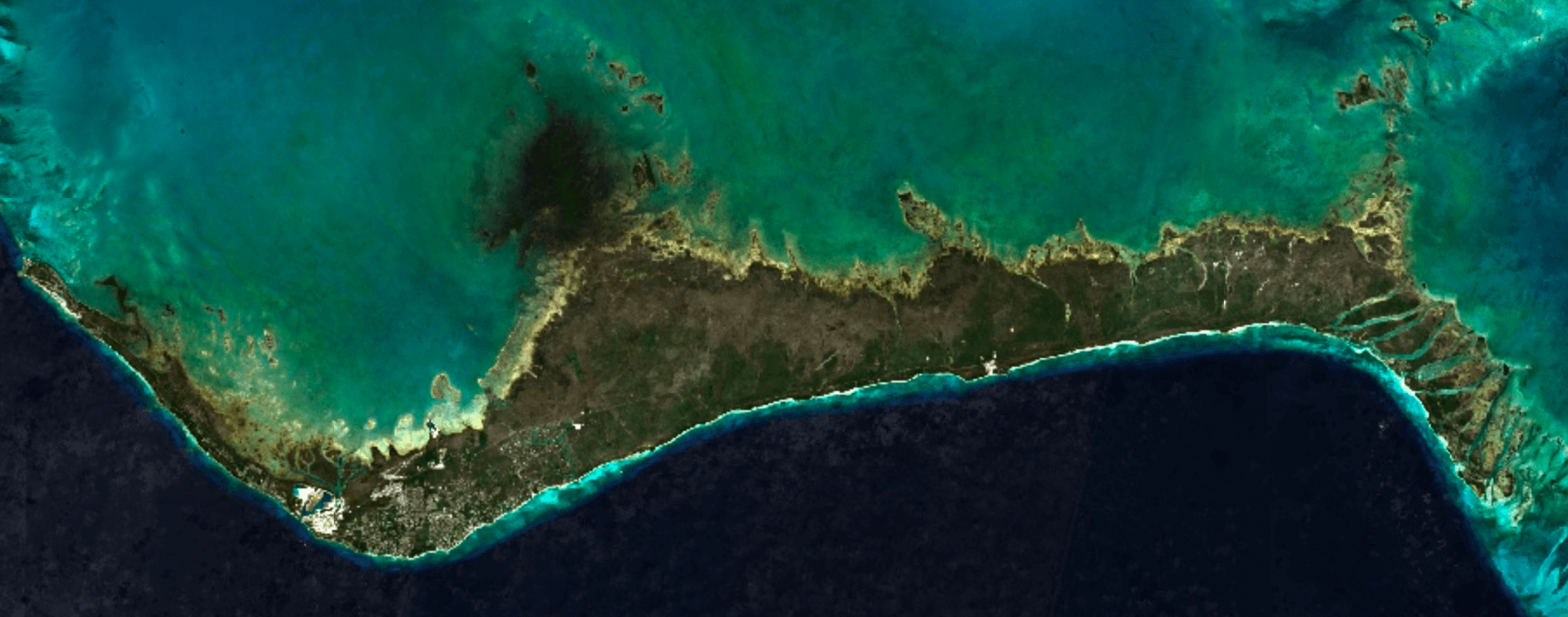

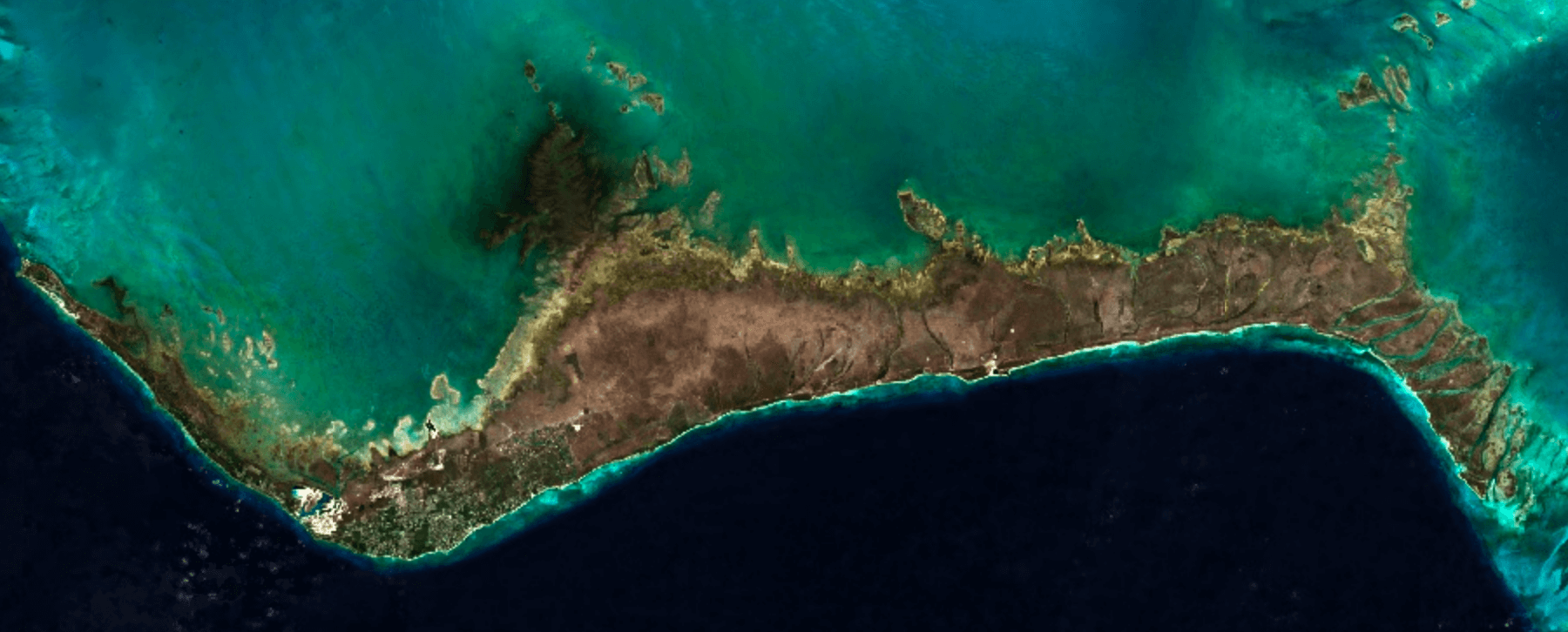

These two Sentinel-2 satellite images illustrate just how dramatically Hurricane

Dorian transformed vegetated landscapes on Grand Bahama. In the “before” image (left), the island is

covered in the verdant green of healthy mangrove forests, coppice forests, and pine forests. In the

“after” image (right), most of the island is denuded and brown. Some forested areas were only

defoliated by the storm, meaning that they temporarily lost their leaves but did not sustain any

long-term damage. However, many more areas suffered complete destruction or long-term damage,

especially on the eastern two-thirds of the island. In this photo essay, I “zoom in” on areas that

exemplify both levels of severity to compare their impacts and recovery trajectories.

This photo shows dead mangroves as far as the eye can see in one location along the

northern coast of Grand Bahama. While many mangroves were killed by Dorian’s 185-mph winds and

20-foot storm surge, many were also killed by the flooding that occurred while the hurricane sat

over the island for more than 40 hours (Cerrai et al. 2020). Mangroves are uniquely adapted to the

periodic and/or partial submersion that comes with living in the intertidal zone and are therefore

more tolerant of saltwater than most terrestrial plant species. However, even mangroves cannot

survive complete, prolonged submersion.

The hurricane dramatically reshaped portions of Grand Bahama’s coastline, like this

segment of Gold Rock Beach at Lucayan National Park. The inlet in the foreground of this photo was

sandy beach before it was washed away during the storm. The storm also destroyed much of the Park’s

coppice forest, as depicted in the background of the photo. “Coppice” is the Bahamian term for

several sub-categories of dry broadleaf forests found throughout the country, and should not be

confused with “coppicing”, the management practice of periodically cutting trees to promote new

shoot growth. Both in the Park and throughout the island, these forests provide important habitat

for many terrestrial animal species.

In addition to providing essential habitat for many marine and terrestrial animal

species, mangroves act as a “first line of defense” against hurricane winds and storm surge. They

also stabilize coastlines against both chronic erosion and acute erosion events (like the one shown

in the previous photograph). All of the mangroves in the foreground of this photo were killed by

Dorian, but their dense root network held the sediment in place and likely helped minimize the

damage to the green, living coppice forest in the background. However, dead mangroves are not as

effective as healthy ones at binding soils or absorbing storm impacts. If and when another hurricane

hits this location before the mangrove forest recovers, much of this land could be at risk of being

swept away, and inland habitats and communities could sustain even greater damages.

Grand Bahama’s pine forests, located farther inland and at higher elevations than

the island’s mangrove and coppice forests, were also severely damaged by the storm. Many pine trees

were snapped in half by Dorian’s 185-mph winds, but many more were killed by prolonged submersion in

saltwater. The pine forests of Grand Bahama and Abaco provide important habitat for many animal

species, two of which are endemic to the islands: The Bahama warbler (Setophaga flavescens)

is found

only in pine forests of Grand Bahama, Great Abaco, and Little Abaco islands. The critically

endangered Bahama nuthatch (Sitta pusilla insularis) is found only in the pine forests of

Grand

Bahama, and many conservationists are concerned that Dorian may have extinguished the species

(Sreekar et al. 2020).

Grand Bahama’s human landscapes, particularly those on the eastern side of the

island, were also dramatically affected by Hurricane Dorian. As of late February 2020, 6 months

after the storm’s landfall on the island, many homes were still severely damaged and uninhabited,

with many families living in tents and other temporary shelters.

Cleanup efforts were also ongoing, with piles of rubble and damaged cars a common

sight on the island’s east side. Abandoned cars and other debris introduce oil, plastics, heavy

metals, and other pollutants to the island’s natural environments (Nwachukwu et al. 2013), further

complicating the recovery process.

Recovery efforts have been hampered substantially by widespread damage to Grand

Bahama’s infrastructure and utilities networks. As of February 2020, much of the eastern portion of

Grand Bahama was still without power. Downed power lines like this one were very common sights along

the Grand Bahama Highway, the main, two-lane road that runs the length of the island.

Flood waters scoured away much of the foundation of this bridge, making it one of

several still closed for repairs as of February 2020. Infrastructure damages have further impeded

recovery efforts by making it more difficult to get equipment and supplies to the communities that

need them.

Freeport, Grand Bahama’s largest city and tourism center, sustained less widespread

structural damage than the island’s eastern end. Most hotels, restaurants, and gift shops were back

open for busines as of February 2020. However, many locations, like this beachfront property, were

still shuttered. Tourism income accounts for 50 percent of the Bahamas’ GDP, and Grand Bahama and

the Abaco Islands are two of the nation’s three most popular tourism destinations (Bahamas

Investment Authority 2020; Deopersad et al. 2020) The islands’ coastal landscapes are central to

many of their most popular tourist activities like fishing, snorkeling, and diving. The hurricane’s

disruption to tourism activity is estimated to have caused tourism income losses of more than $325

million USD for the Bahamas as a whole, including more than $28 million USD on Grand Bahama and more

than $270 million on the Abaco Islands (IDB 2020). Downturns in international travel during the

COVID-19 pandemic have further crippled the islands’ tourism industries, with an estimated 50 to 60

percent decrease in Bahamian tourism income attributed to the pandemic (Mulder 2020).

This photo depicts one of several enormous piles of queen conch (Lobatus

gigas)

shells in McLean’s Town, the self-proclaimed “Conch Cracking Capital of the World.” Spiny lobster

(Panulirus argus) and conch were the second and sixth most valuable Bahamian commodity

exports in

2018, accounting for 14 percent and 0.8 percent of total export income for that year, respectively

(Bahamas Department of Statistics 2019). In addition to being two of Grand Bahama’s top commercial

exports, conch and lobster are also important subsistence foods for many locals. These and other

marine species of commercial and subsistence importance depend on healthy seagrass and coral reef

habitats, which in turn depend on healthy mangrove forests. With so many local livelihoods directly

and indirectly connected to mangrove forests through the tourism and fishing industries, the

recovery of these coastal landscapes will be essential to the recovery of Grand Bahama’s human

communities.

As with all natural disasters, the impacts of Hurricane Dorian were unevenly

distributed, from forest stand-scale to island-scale and everything in between. This picture shows a

mangrove forest on Grand Bahama’s southern coast with a mix of both healthy and dead mangroves. Just

as help from island, national, and international communities will be essential to the recovery of

places like McLean’s Town, the regeneration of impacted mangrove forests will depend largely upon

recruitment of seedlings from adjacent, healthy stands. However, complete recovery of

hurricane-impact mangrove forests can take 10 to 20 years (Imbert 2018; Krauss and Osland 2020) in

areas like this one that are conducive to seedling recruitment, with healthy trees intermingled with

dead ones. In mangrove forests that were totally destroyed by the hurricane, recovery may take even

longer.

Many years of recovery lie ahead, but the process had already begun in many

mangrove, coppice, and pine forested areas. This photo shows a mangrove seedling (called a

propagule) that has taken root amidst a stand of dead mangroves. Local, national, and international

organizations are also working to facilitate the recovery of these coastal landscapes. For example,

the Bonefish and Tarpon Trust (an international sportfish conservation organization based in

Florida) and the Bahamas National Trust are coordinating a mangrove restoration program that

involves the planting of propagules in strategic locations to enhance the natural regeneration

process. The mangrove maps resulting from our field work and satellite imagery analysis are helping

to identify priority areas for restoration.

Summary

As demonstrated in the preceding photos, both the human and natural landscapes of Grand Bahama and

Abaco were devastated by Hurricane Dorian. However, even before Dorian the lines between “human” and

“natural” landscapes were always porous and fuzzy. Just as the livelihoods of many human communities

are dependent upon the provisions of coastal and terrestrial ecosystems, the sustainability of these

ecosystems is directly mediated by human activity. Many people on the islands face a long, uncertain

recovery process. But one thing is for sure: the rejuvenation of Grand Bahama’s and Abaco’s natural

environments will be vital to the recuperation of its human populations.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Michael Steinberg for his invaluable collaboration on this project. Both this photo

essay and the broader mapping effort are joint endeavors that would not be possible without his

wisdom and exertion. Thank you to the Bonefish and Tarpon Trust (BTT) for funding this field work.

In particular, thank you to Justin Lewis, BTT’s Bahamas Initiative Manager, for sharing his boat,

his time, and his expertise with us during the field work. Thank you to Shelley Cant-Woodside,

Director of Science and Policy at Bahamas National Trust, for her assistance and insights. Last but

not least, thank you to two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

References and Further Readings

- Bahamas Department of Statistics. 2019. Foreign Trade Publication 2018. Nassau, the Bahamas:

The Government of the Bahamas. [https://www.bahamas.gov.bs/wps/wcm/connect/

c2a16645-b29a-4e87-8289-81f876b00970/Annual+Foreign+Trade+Report

+2018.pdf?MOD=AJPERES].

- Bahamas Investment Authority. 2020. Economic Environment. Nassau, the Bahamas: The

Government of the Bahamas. [https://www.bahamas.gov.bs/wps/portal/public/About%

20Us/About%20The%20Bahamas/Economic%20Environment/].

- Cerrai, D., Q. Yang, X. Shen, M. Koukoula, and E. N. Anagnostou. 2020. Brief communication:

Hurricane Dorian: automated near-real-time mapping of the “unprecedented” flooding in the

Bahamas using synthetic aperture radar. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 20: 1463-1468.

- Deopersad, C., C. Persaud, Y. Chakalall, O. Bello, M. Masson, A. Perroni, D. Carrera-Marquis,

L. Fontes de Meira, C. Gonzales, L. Peralta, N. Skerette, B. Marcano, M. Pantin, G. Vivas, C.

Espiga, E. Allen, E. Ruiz, F. Ibarra, F. Espiga, M. Gonzalez, S. Marconi, and M. Nelson. 2020.

Assessment of the Effects and Impacts of Hurricane Dorian in the Bahamas. Washington, D.C.:

Inter-American Development Bank.

- Imbert, D. 2018. Hurricane disturbance and forest dynamics in east Caribbean mangroves.

Ecosphere 9 (7): e02231.

- Krauss, K. W., and M. J. Osland. 2020. Tropical cyclones and the organization of mangrove

forests: a review. Annals of Botany 125: 213-234.

- Mulder, N. 2020. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism sector in Latin America

and the Caribbean, and options for a sustainable and resilient recovery. International Trade

Series, No. 157, [LC/TS.2020/147]. Santiago, Chile: Economic Commission for Latin America and

the Caribbean [ECLAC].

- Nwachukwu, M. A., B. Ntesat, and F. C. Mbaneme. 2013. Assessment of direct soil pollution in

automobile junk market. Journal of Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology 5 (5): 136-146.

- Sreekar, R., K. Sam, S. K. Dayananda, U. M. Goodale, S. W. Kotagama, and E. Goodale. 2020.

Endemicity and land-use type influence the abundance-range-size relationship of birds on a

tropical island. Journal of Animal Ecology. [https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13379].

- Zegarra, M. A., J. P. Schmid, L. Palomino, and B. Seminario. 2020. Impact of Hurricane Dorian

in the Bahamas: A View from the Sky. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank.