Preserving Oaxaca

In 1987 UNESCO added the city of Oaxaca de Juárez, Mexico (hereafter Oaxaca) and the nearby archaeological site Monte Albán to its World Heritage List. The listing reflected the size and successful preservation of the Oaxaca's urban heritage. Oaxaca's 240 central city blocks comprise the second largest colonial core in Mexico. Oaxaca and Monte Albán combine to make the area one of Mexico's leading non-resort tourist destinations.

The preservation of Oaxaca's urban heritage has had many authors. One, however, is distinguished for his early recognition of the need to protect the city's colonial landscape, and because of his enduring efforts on its behalf. Dr. Juan Ignacio Bustamante Vasconcelos (1917-2001) lived a life marked by sterling professional achievements and a boundless curiosity about his native state, Oaxaca. He wore many hats, but foremost, he was a medical doctor. He served the Mexican military in that capacity for 25 years while also practicing pediatrics in Oaxaca. His loyalty to Oaxaca led him to serve as a legislator, 1964-1967, for the district that included the city of Oaxaca.

Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos was also a shutterbug and shot, developed, organized and captioned more than 10,000 photographs between 1948 and 1973. These photographs are a record of his life and Oaxaca. They reveal his professional development, his interests, his family and friends and his genuine concern for landscapes and people throughout Oaxaca. From the photographs and his captions we learn that he was a mountain climber as a young man who became an environmentalist by the 1950s, and photographed deforested and eroded landscapes. He also sought out archaeological discoveries and frequently photographed local excavations. He studied colonial church architecture throughout the state and promoted the preservation of Oaxaca's colonial architecture. In short, his list of interests was long.

In his later years Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos focused on a lifelong interest, the study and preservation of the history and cultures of Oaxaca. He authored two books on the topic, but his greatest contribution was founding the Fundación Cultural Bustamante Vasconcelos with his brothers in 1984. They created this space in Oaxaca’s historic city center, opened it to the public, and filled it with their personal archives, which included their personal libraries, archaeological artifacts and their collections of photographs. The Fundación’s is Oaxaca’s most important source of historic images of the city and state and is used by international and local scholars involved in preserving Oaxaca’s local historical memory.

Rephotography or Caminando en los Pasos...

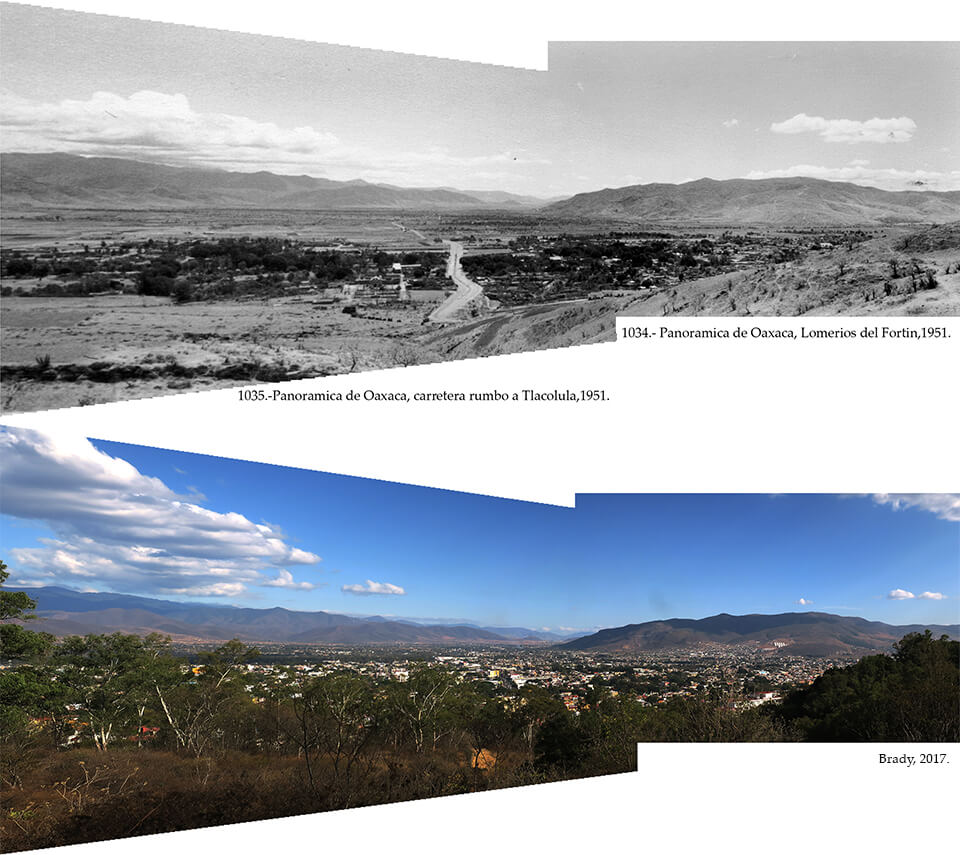

Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos’ daughters manage the Fundación. For the past five years they have helped me study the thousands of photographs taken by Doctor Bustamante Vasconcelos as part of a rephotography project. The Fundación has presented several expositions of my rephotographs in a continuing series called Caminando en los Pasos del Dr. Juan Ignacio Bustamante Vasconcelos (Walking in the Footsteps of Dr. Juan Ignacio Bustamante Vasconcelos). I chose that name because it captures the nature of the work. To produce a good rephotograph, I have to locate where the doctor stood when he took the original photograph. Since 2016 I have walked Oaxaca’s streets, hiked the ridge lines that surround Oaxaca’s Central Valleys and explored remote mountain communities throughout the state, looking for the place the doctor stood when took a picture and made a record of a landscape. Then I take a picture and make a new record. The repeat images in this photo essay rarely resulted from a single visit to a site. Rather, I usually had to make multiple visits, taking multiple photographs until I got it right. Paired together our photographs show how landscapes have changed during the past fifty to seventy years. The photo pairs in this photo essay focus on the landscapes of Oaxaca's colonial core.

Protecting Oaxaca from what?

By 1950 the doctor and his brothers were promoting preservation of Oaxaca's colonial landscapes. They argued for the creation of preservation policies at professional meetings. Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos also sought to advance preservation by cultivating an appreciation for historical landscapes among local residents. In 1952, he organized a photographic excursion for the Club Fotografica de Oaxaca. In the accompanying pamphlet that he wrote, he directed excursionistsas to multiple sites in the city to observe representative examples of the architecture that he wanted to protect. What exactly did he want to protect? And, from what? This passage from the pamphlet explains:

“la austera sencillez de sus contrucciones y el hermosa forjado de sus antiguos hierros en ventanas y balcones, que en los ultimos anos han comenzado a desaparecer al empuje de un modernismo muy mal entendido al que urge poner un dique para salvar la belleza de la poblacion.”

“the austere simplicity of Oaxaca's architecture and the beautiful old wrought ironwork in windows and balconies, which in recent years has begun to disappear due to the push of a very poorly understood modernism that urgently needs to be stopped to save the architectural beauty for Oaxaca's residents.”

Already in the 1950s the young doctor was seeing Oaxaca's colonial landscape being replaced by Modernist architectural ideas that emanated from Mexico City. During this decade he used his camera to record what he feared would disappear. His photographic archive is replete with images of houses, balconies and ornate wrought iron grillwork. It also includes his occasional lamentation about the removal of a treasured historic structure.

Oaxaca Then and Now

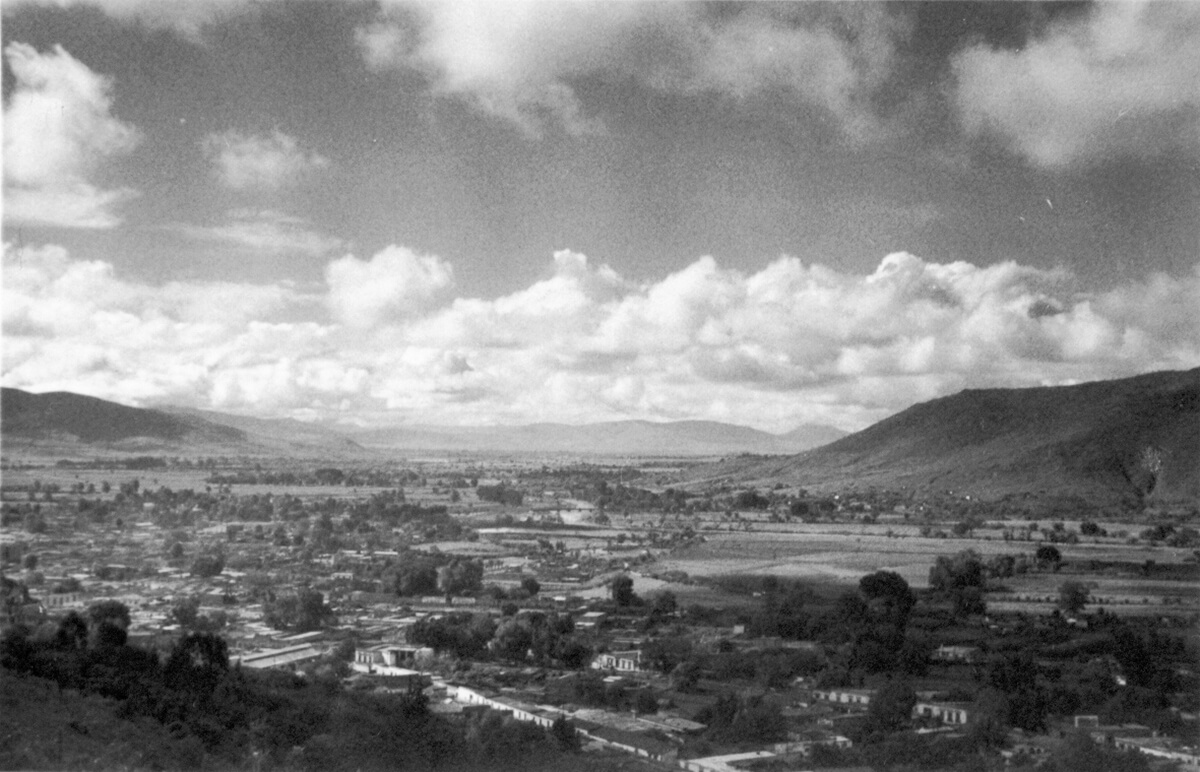

Rephotographing images that the doctor took in the 1950s reveals both change and persistence. At the panorama or landscape scale, change is undeniable. Image #996, reveals that the agricultural landscapes that surrounded Oaxaca seventy years ago have been erased by a sort of gravity-defying urban glaciation that has crept from the settlement's historic core, pushed across the Atoyac and Salado rivers, filled in the valley floor and sprawled up the western slope.

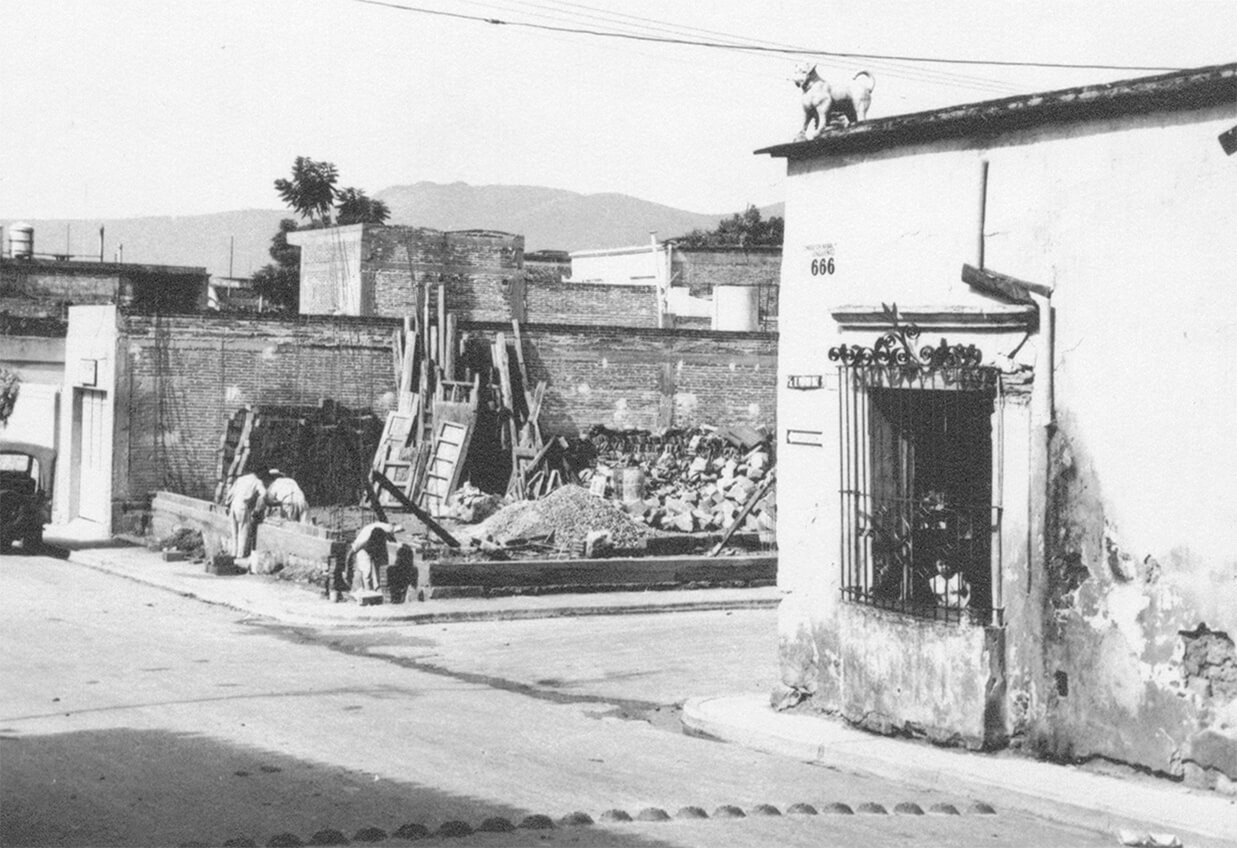

However, at the street corner scale in Oaxaca's historic core, persistence is often the story. Images #800 and #803 demonstrate that some of the historic structures that Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos photographed seventy years ago have not suffered the fate of the structure he captured in image #3737.

Yes, evidence of decay can be found in Oaxaca's historic core. Such as in image #758.

However, instances of decay are balanced by many cases of preservation such as that shown revealed in image #371.

Mapping Landscape Change and Persistence

Location is essential for observing changes in a landscape. The map below provides that context. Each place marked on the map indicates a location where Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos took a photograph between 1950 and 1960. The doctor's images are linked to each placemark, as are my photo pairs. The number that accompanies each placemark designates its location in the Fundacion’s photograph collection.

The map is designed as a photo tour. It begins with panoramic photographs taken from the eastern slope of Cerro del Fortín, which looms above Oaxaca's colonial grid of streets. The panoramas show a compact city embedded in agricultural valley. The tour then leads down into Oaxaca’s compact colonial core and shows some of the historical highlights that Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos sought to protect. Viewers should tour by clicking on individual map markers, which will open each repeat image pair and reveal captions and additional notes to guide viewers' viewing. Clicking on the magnifying glass icon will enlarge the photo pair for closer inspection.

El Marquesado is a colonial-era neighborhood that was adjacent to colonial Oaxaca City. It is in the lower foreground of the original picture, nestled between the western slope of Cerro del Fortìn and the farmland on the western side of the Rio Atoyac. The archaeological site Monte Albán is perched, just out of the frame, on the slope to the right. See how settlement has spread to this UNESCO World Heritage site’s boundary.

Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos centered this panorama on the Iglesia Santo Domingo, which used to dominate views to the east from Cerro del Fortín. Seventy years later the sprawl that has covered the valley and climbed the slopes above San Antonio de la Cal distracts from the church’s grandeur.

And to the south from Cerro del Fortín, a similar story.

Perhaps Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos enjoyed climbing because of the panoramic views from the peaks. He often created connected panoramas, such as 1034 and 1035, simply by rotating and shooting. Photoshop’s Photomerge tool stitches together these shots to broaden the perspective. The hike up Cerro del Fortìn is popular because it is so close to the city center. However, unlike 70 years ago, many panoramas are blocked by the successful grassroots reforestation projects.

The doctor also enjoyed summiting buildings and recording vistas like this one from atop the Templo de las Nieves. Looking northwest, back at Cerro del Fortìn, it is clear that Oaxaca has built up as it has sprawled out. The layer of mostly one-story flat-roofed buildings that comprised much of the colonial city has been complicated by multi-story buildings that diminish the exalted heights of church domes and bell towers. Candy cane satellite towers and the white vinyl tarp draping the Auditorio Guelagetza further obscure the former separation between the city and the Cerro.

Standing atop a building on Calle 20 de Noviembre Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos centered his panorama on the Basilica de la Soledad resting at the southern foot of Cerro del Fortìn and revealed Oaxaca’s rooftop, azotea, landscape. Upward growth of new buildings conceals the azoteas. Continued growth of Oaxaca’s plaza trees, the Laureles de la India (Ficus microcarpa), hide la Soledad’s ornate facade and restored bell towers and indicate public spaces like Plaza de la Danza and Jardin Morelos.

Taken from the same spot as #982, #983 shows persistence in the commercial streetscape along Calle 20 de Noviembre. It also reveals the progress of reforestation on Cerro del Fortìn and shows how Oaxaca’s primary cultural event and tourist attraction, the Guelagetza, announces itself in the landscape, a great white cloud of vinyl that floats above the auditorium that hosts the dance festival.

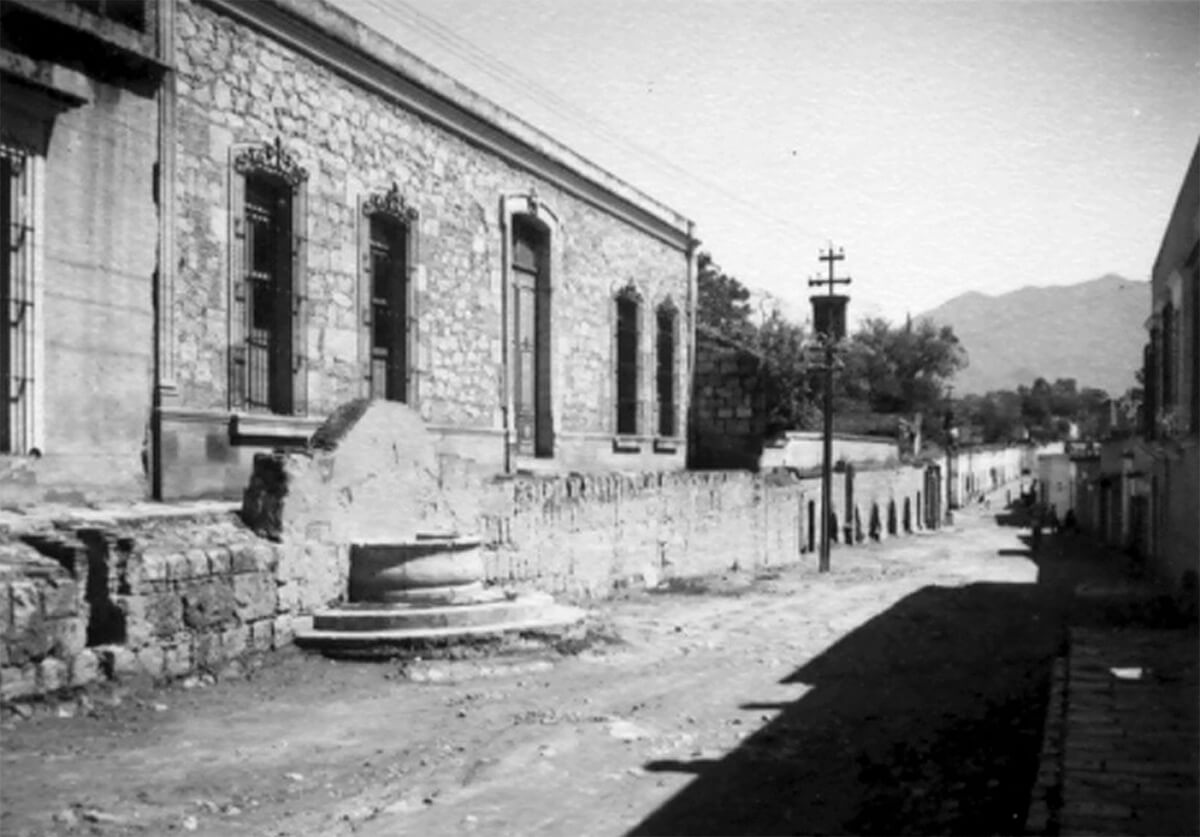

On the western edge of Oaxaca’s historic core the doctor captured a simple, but necessary component of colonial infrastructure, the circular fountains, fuentes, that distributed fresh water brought from San Felipe by the aqueduct. Though out of use, the aqueduct remains and several of the fountains have been replaced by faithful reproductions. The house facade to the right of the fountain is a common sight on the fringes of the historic district. A landowner has begun renovating a historic structure. The facade is done but it hides an interior pile of rubble and colonizing plants. Since 2006, graffiti has accompanied recurring bouts of civil unrest.

A circular seam that marks the boundary between new and old concrete on the sidewalk along Calle de la Constitución puzzled me until I found Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos’ photograph. The seam is the only trace of the fountain. The photo pair demonstrates that decrepit colonial structures can be revived to a simple, colorful elegance.

At the intersection of Avenida Morelos and Avenida Porfirio Dìaz the doctor captured two examples (#800 and #804) of the wrought ironwork that he worried would be disappear. This location is only three blocks from Oaxaca’s central plaza, zocalo, and, thereby, a prime focus of historic preservation.

At a nearby intersection he recorded three examples of the urban landscape that he felt should be saved. The buildings in images #801, #802 and #803 remain little changed. However, the automobile traffic that chokes Avenida de la Independencia, the historic district’s main east-west thoroughfare, distracts an observer from the buildings’ graceful proportions and refined grillwork. So too does the ghost bike that hangs from light pole on Calle JP Garcia. It marks the location of a cyclist fatality.

Nine years after Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos took the photos previously presented on this map tour, he observed a case of demolition that he claimed was “against Oaxaca.” This corner shows an instance of Modernism replacing the colonial landscape that he valued.

However, the doctor would be pleased by the preservation and restoration that has made Calle Manuel Garcia Vigil and its extension Calle Rufino Tamayo a favorite dining, strolling and shopping street. In the background the restored aqueduct extends northward to San Felipe.

The popularity of the aqueduct confirms Dr. Bustamante Vasconcelos’ belief that Oaxaca’s colonial landscape should be preserved. However, I am not certain that he foresaw that historic preservation would be foundational to Oaxaca’s tourist economy.